Dr Max Graham, Founder and CEO of Space For Giants discusses the importance of protecting elephants in the wild and the new partnership with Gemfields and Net-A-Porter.

Dr. Max Graham

International conservation organisation “Space for Giants” recently partnered with Gemfields and Net-A-Porter on a project that saw the two luxury companies raising awareness of the company’s work for African wildlife conservation. The project, titled “Walk for Giants”, saw the brands create sustainable capsule collections with the proceeds being donated to Space for Giants and its work. The two exclusive capsule collections consisting of a 44-piece jewellery and watches collection and a series of 15 sustainable looks from Net-A-Porter. Proceeds from the collection will bring critical support to protect Africa’s elephants and their natural habitat.

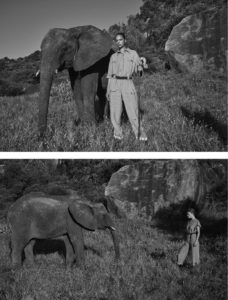

Space for Giants is committed to securing the ecological and economic value that nature conservation offers and through protecting the great wildlife landscapes of Africa, they can help protect the continent’s remaining elephants that need these habitats to survive. Especially in this time of crisis, when travel and tourism are impacted, wildlife and natural habitats are even more vulnerable to exploitation. The company was founded by Dr Max Graham. Graham founded Space for Giants in 2011 in response to poachers killing several of the elephants he was studying during conservation research for Cambridge University. He has since been leading efforts to combat the illegal ivory trade in Kenya.

In 2015, to scale up the conservation tools developed by Space for Giants in Kenya, to the continental level, Max founded the Giants Club, combining political, social and financial muscles with the goal of protecting at least half of Africa’s elephants and the landscapes they depend on. Today the Heads of State of Botswana, Gabon, Kenya and Uganda are the Presidents of the Giants Club and its members are among the most influential philanthropists and business leaders in the world. Space for Giants is working on projects in nine African countries with an increasing focus on attracting conservation and tourism investment to sustain the continent’s remaining natural ecosystems. The Walk for Giants project is the latest in Graham’s journey of raising awareness on a global scale and helping industries such as fashion and jewellery to understand the importance of their actions. We find out more with Dr Max Graham.

What can you tell us about why you decided to start your company Space for Giants?

After University I went to volunteer for an old man who owned a small ranch in Kenya. Shortly after I arrived he showed me around the property that he was entrusting in my (very young and truly incapable) hands while he and his wife went to visit his brother in South Africa. Just before he got into the rusty old plane he yelled at me, “and please do something about these elephants”. Intrigued, I asked around and discovered that a small herd of around 100 elephants passed through the ranch several times a year on their way to Mount Kenya. I completely forgot all about my responsibilities to the ranch and spent the next three months following the elephants, learning about their behaviour and movement patterns. Those three months connected me to elephants in a powerful way that is difficult to describe and through my subsequent PhD research at Cambridge University, I discovered just how vulnerable their lives are and what it could take to ensure they have a future. When some of the individual elephants I got to know during this research were poached I founded Space for Giants – not just to combat the illegal wildlife trade but ultimately, to ensure that these iconic animals have a future in the wild in a world that is increasingly dominated by humans.

Why did you decide to partner with Gemfields and Net-A-Porter for this project and what are you hoping to achieve from it?

In this campaign, two key players in the jewellery and fashion industries have come together to support the conservation of Africa’s wildlife and natural landscapes, with the proceeds from the sale of the capsule collections going towards the frontline conservation work we do. However, it is our objective with this campaign to demonstrate to the fashion industry and to customers, that a unit of consumption can be converted to a unit of conservation. This is not only good for conservation but is critical for business in an increasingly environmentally conscious marketplace. Herein lies the opportunity, which is that big brands will soon, we hope, start investing in the protection of vital natural ecosystems. These ecosystems’ natural services will not only offset their carbon emissions but also make their products more compelling and competitive among increasingly environmentally sensitive consumers. If this were to happen, then perhaps the future of the world’s remaining giants will truly be secure, forever.

How do you think the values of your company align with that of Gemfields?

Gemfields place sustainability and the protection of the environment at the centre of their operations. This is very much aligned with our thinking at Space for Giants. We believe that for the long-term health of the planet, this is the approach that most businesses in any industry should adopt. The Walk for Giants project captures the essence of that commitment from both organisations.

As a company Net-A-Porter is particularly concerned with sustainability – is this something that you find aligns well with your company?

Indeed it is. Times have changed and it is increasingly unacceptable for companies to not invest in social and environmental sustainability. Net-A-Porter is demonstrating that it is indeed possible to be a big and highly successful business, whilst being conscientious enough to implement sustainable practices and provide direct support to the protection of nature and wildlife.

What are some of the issues wildlife in Africa is facing today that we should be aware of?

Africa’s wild places and their wildlife are some of the most bio diverse ecosystems left on Earth. They have great value both ecologically and economically to people, to countries, and to the planet. But they are under threat.

Elephants are threatened mainly by three factors – poaching for their tusks, loss of habitat and conflict with farmers over crops and water. Rhinos face a similar poaching problem for their horns. Lions are threatened by loss of habitat and conflict with livestock farmers, whilst great apes such as gorillas are threatened by poaching and habitat degradation.

There is one underlying threat that all these iconic species face that will determine their survival – loss of habitat in a rapidly modernising continent. Our work at Space for Giants is geared towards securing these natural landscapes that wildlife depend on, creating great value for African nations, their citizens and the planet.

Our work is focused on finding new ways to fund the protection of these landscapes forever so they can continue to bring their benefits for generations to come.

Tell us about your first experience with elephants?

The first time I encountered an elephant I was 17 and the moment was as dramatic as it was fleeting. I was travelling with my girlfriend at the time, and her family, along a dusty game track through Tsavo National Park when quite suddenly an animal so large appeared before us that it seemed as if it had sliced the universe apart with its presence. Shattering any illusions of comprehension that I may have ha it stared penetratingly into our beings and then with a disapproving wag of its huge head, a powerful snap of its sail-scaled ears and a bone-shaking shriek from its trumpet, it disappeared. From that moment elephants held an acute, addictive fascination for me.

What is your biggest achievement so far with Space for Giants?

Space for Giants helped pioneer an approach to combatting illegal wildlife crime that contributed to the virtual elimination of elephant poaching in central Kenya where the organisation was first founded. It helped to increase conviction rates in the entire country from 26% to over 90% in just 4 years. This approach has now been scaled up into nine countries across Africa.

We have also helped to design and deploy new smart electrified fences to combat the major problem for smallholder subsistence farmers of crop-raiding by elephants. We are about to complete a 400km wildlife fence, in partnership with the government that was first conceptualised by experts in 1986 to protect the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of smallholder farmers in central Kenya. As no one had truly stepped up to the challenge of getting this work done, we took it on in 2010. Now ten years later, we are but a few months away from putting in the final fence post.

But my proudest achievement to date is our work to buy a private land that was a critical elephant refuge and, in partnership with The Nature Conservancy, turn it into a protected area; Loisaba Conservancy which is owned and managed by a not-for-profit trust. This conservancy is now a thriving eco-tourism destination, a hub for community support and secure home for elephants and all the other species that share their range. The process of creating this conservancy spawned a conservation and tourism investment process that is now being deployed in partnership with Heads of State in four African countries. The positive impact this process is having on making wild places valuable to local people and national governments is what I am most proud of as it is this value that will ensure elephants and indeed all wildlife will endure in our world.

What would you still like to achieve that you haven’t been able to do yet?

I would like for Space for Giants to co-manage several iconic protected areas with National Governments with the objective of turning them into world-class conservation assets and hugely valuable engines for driving value to local citizens and national governments.

What is the biggest challenge you face as a company?

Our work is as exciting as it is challenging. We have numerous opportunities to innovate and find solutions to existing conservation threats, but inadequate funding often impedes this. The financial climate right now makes things especially difficult, and as people on the frontline, we still have a responsibility to protect wildlife, despite the drastic decline in available resources.

What is the motto you live by?

There is always a way.

Can you share with us a story or moment that has really inspired you during your travels?

I once sailed on a dhow with a small crew of Swahili sailors to a very remote inlet on the North Kenyan coast near Somalia. The insecurity here meant this beautiful coastline was astonishingly unspoilt, with shallow warm water teeming with life, including large pods of bottlenose dolphins. I found myself in disbelief at the natural beauty here. We anchored off a tiny beach to rest and as we lay there a spearfisherman walked past us with a net of fish. I complimented him on his catch and he stopped in his tracks and insisted that they were a gift for me. He refused any payment and went on with his day. Where nature is unspoilt, people are unspoilt.

This year has been a strange one for all – what is a lesson you‘ve learnt or something that you will take away from this period?

While we scramble to get ourselves out of this mess, it is critical to remember we are in this situation because of the exploitation of nature, where wild animals have been captured to supply a highly lucrative international illegal trade in their parts. My biggest lesson is that we cannot go back to ‘business as usual’ – I do hope this pandemic has made us as humans realise that the protection of nature is not just the responsibility of conservationists. 2020 has taught us that we must all come together to promote a healthy earth; otherwise, the consequences of destroying nature have demonstrably proven to be catastrophic.

How has this year impacted the work that you are doing in Africa?

The wildlife conservation sector in Africa is largely dependent on income from tourism, philanthropy and government funding. With the COVID-19 crisis, tourism income has disappeared and philanthropy and government funding are rapidly declining with the global economic downturn. This is impacting the delivery of essential frontline conservation services in African protected areas and the livelihoods supported by employment in tourism and the related industries. This means there is a greater pressure on natural ecosystems from habitat exploitation and the illegal wildlife trade. As a consequence, we are facing a new and very serious conservation crisis.

Do you think this time has encouraged the world to reflect on nature?

I do hope so. Clearly, the consequences of not protecting nature have proven to be devastating through the unprecedented loss of lives, a global public health crisis and the collapse of the global economy. The time for action is now.

You have great support from international politicians and heads of state but how can you raise more awareness of these issues globally?

We work with local, national and international partners to drive home the urgency and necessity of immediate action to preserve Africa’s natural landscapes and their wildlife. We have an African Journalist Fellowship programme that allows us to mentor and work with environmental and conservation-focused African journalists, enabling them to better tell conservation stories in their own authentic voices to audiences in their countries and beyond.

We seek and find opportunities that allow us to engage with other conservation organisations, governments, philanthropists, as well as other industries such as fashion to generate interest and support for conservation. One of these campaigns is Walk for Giants. Additionally, we have a longstanding partnership with ESI Media allowing conservation stories to reach 120 million people worldwide every month.

Tell us about your decision to move to Kenya and how your family grew?

Kenya actually created my family. While I was working there, a smart beautiful graduate joined me as a volunteer in 2010 and we subsequently worked together on her PhD research on human-elephant conflict. A few years later we were married and had two small children who have known no other life but one in the bush.

Talk us through your daily routine.

If I’m home I get up around 6 am with the kids, try and do a little exercise on my veranda that looks across to Mount Kenya. We have breakfast together and then I spend most of my day checking up on our conservation projects either in person or over the Internet. In the late afternoon, I often go for a drive with my wife and kids and we look for wildlife and typically find a spot under a tree for a bush dinner. When we get home and after I have wrestled the kids to sleep, I either do some more work or I’m on calls to our strategic partners and supporters in other time zones until late. Because so much of what I do today is about building strong relationships with key individuals who can help us to win this conservation battle, I spend a huge amount of my time on the road.

What do you love most about what you do?

I love visiting remote, wild, wilderness where nature is undisturbed.